A (very long) interview with Robert Taylor covering his life and career. Taylor is a computing visionary that oversaw innovations such as Personal Computing, GUIs and (inter)networking.

The best way to predict the future is to invent it. -- Alan Kay

Recently I have written a little bit about Smalltalk, and in my enthusiasm I got hold of a book called Dealers of Lightning by Michael Hiltzik. It covers the rise and fall of Xerox's Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), the research center from which Smalltalk emerged.

I initially read it to learn more about the context in which Alan Kay imagined Smalltalk and to find out who was the Executive-X he mentioned in The Early History of Smalltalk (it was Jerry Elkind). However I ended up coming away with a lot more. In particular, a new appreciation for a number of scientists I previously knew very little about. Scientists that are almost single handedly responsible for the shape of modern computing.

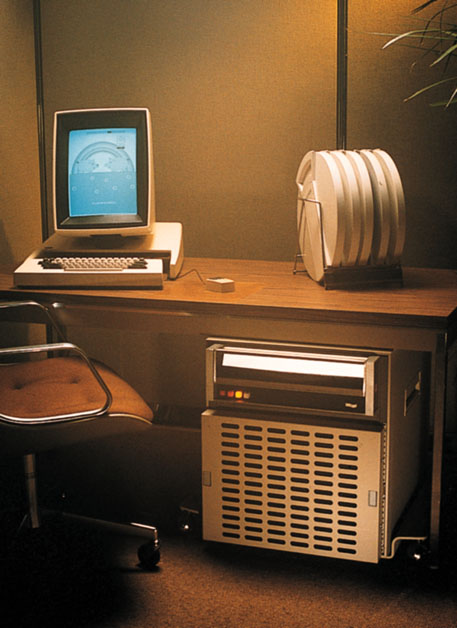

I grew up in the 80s so I have no real personal appreciation for computing as it was before say, 1984. I had an IBM clone (an Amstrad) and a VIC20. At school we have Commodore 64s/128s to play with. So for me, a computer has always been something that sits on your desk, you turn it on and you type away and stuff pops up on the screen. But right up until the late 70s this paradigm was considered absurd. Wasteful even. It took the vision of Alan Kay and the technical genius of Chuck Thacker and Butler Lampson along with the almost unlimited cash of Xerox to realise.

The book opens up by transporting the reader back in time to the late 60s and lays out the genesis of PARC. It then proceeds in roughly chronological order with each chapter focusing on one of the scientists and/or their inventions. The book closes by looking at some of the reasons why Xerox couldn't transform its research into viable products. Nominally the story is about what Xerox PARC did, however Hiltzik couches everything in terms of the scientists and it is his ability to bring these characters to life that makes the book so riveting to read.

One of the most striking individuals of the story is the Impressario Robert Taylor, a man who as much as anything can be considered the grandfather of the Internet (nee ARPANET). The Kays, Thackers and Lampsons of the story are the geniuses but genius needs direction and at times support. This is the role Bob Taylor played. The story of PARC for better and worse revolves around him and his relationship with the researchers that shared his vision of interactive computing and those whether in his or the other labs, or in management, that well didn't.

The Computer Science Lab (CSL) was a collection of engineers who weighed everything pitilessly against the question: How will this get us closer to our goal? They had commited themselves to developing Xerox's Office of the Future and anything that diverted their attention or served an alternative goal had to be discarded or obliterated.

It is Taylor's utterly single minded vision of interactive computing that drives much of the success and much of the drama of PARC. Taylor was in continual combat with the other labs for resources and funding and inevitably with his managers George Pake, Jerry Elkind and eventually Bill Spencer. But that was outside his lab. In it, he was the oil that kept the cogs turning and among his staff he was considered a unique and brilliant manager of researchers. It is on this skeleton of contradiction and conflict that the guts of the story of PARC hangs.

The book contains a number of particularly powerful scenes. Two particularly stuck out for me. The first is Alan Kay, his vision for a Personal Computer brusquely put down by CSL Manager Jerry Elkind, falling into a depression. Alan Kay is well known for his brilliance and verbal flourish but Hiltzik does well to also bring home his vulnerability in a way a modern reader would not expect. Kay would ultimately realise his vision of a Personal Computer - with the help of Taylor's CSL - while Elkind was seconded away from PARC on a Xerox taskforce. We tend to recall Kay's assertive (and largely proven) views on Computing. It is unexpected and moving then, particularly with the benefit of hindsight, to see him doubt himself and his ideas before they were fully realised.

The other scene involves Adele Goldberg, co-developer of Smalltalk, and her reactions to Apple's infamous raid on PARC. If you've ever seen The Pirates of Silicon Valley you might have a feel for how this all went down. But Hiltzik's account of it conveys such a sense of dread and hopeless frustration that the movie never came close to recreating.

By the end of the book Taylor's time at PARC draws to a close and with his departure so too does the most storied era of PARC. Scarcely six months after Taylor's forced resignation, the majority of his lab also resign and either follow him to Digital Equipment Corporation (creators of the famous PDP series of minicomputers), or join one of the many startups blooming in Silicon Valley following the success of IBM and Apple's Personal Computer products.

Dealers is fundamentally a story about people that just happen to be in technology - rather than a book about technology itself. It is a human story. It is about what happens when you take the cream of a generation's scientific talent put them in one place and throw lots of money at them. It is about what happens when you combine a visionary maverick with the proneness to credentialism by academically minded administrators. It is about what happens when you have corporate management that want to embrace change but either do not understand it, or worse, fear it.

It is the book's focus on the people of Xerox and PARC particularly, their feelings, motivations and backgrounds that brings this extraordinary tale of modern computing's birth to life.